How Did Masking Impact The Deaf and Hard of Hearing?

Our debates about masking excluded this community.

As of March 1st, Virginia’s public schools will no longer require students to wear face masks. The demise of the mask mandates was settled by the November election; the state’s new Republican Governor, Glenn Youngkin, quickly signed into law an executive order ending masking. When that order came under dispute, he worked to pass a bipartisan law winning a parent opt-out for students.

While the Virginia branch of the American Civil Liberties Union has decided to sue the state, arguing that the move “shows a reckless disregard for students with disabilities across Virginia,” the legal maneuver is unlikely to succeed.

The most vociferous opposition to ending the mandates has come from Northern Virginia, the region of the state that is most Democratic. That’s not a surprise at at this point. Early in the pandemic, COVID-19 mitigation policies became polarized to such an extent that you could predict the status of school closures not by the severity of the disease at the moment but by partisan leaning of the district and the strength of teachers unions.

Since the culture of masking emerged in the United States, opponents of mandates have argued that they aren’t proven to significantly reduce the spread of COVID-19; proponents have argued that these mandates are essential to protect people from the spread of the virus and that masks are only a small imposition on personal freedom to begin with.

When it comes to masks in schools in particular, both sides have little research to draw from because the vast majority of research on COVID-19 has been focused on adults; this makes some amount of intuitive sense because the disease is on average much more severe for adults than it is on children.

The British government, however, conducted its own review of studies of the use of masking in schools and found the evidence inconclusive about health effects. Interestingly, the British also conducted a broad survey of students to query them about how they felt about using masks:

A survey conducted by the Department for Education in March 2021 found that pupils had a somewhat positive attitude towards wearing face coverings. Pupils generally agreed that face coverings made others (87%) and themselves (70%) feel safe. However, 80% of pupils reported that wearing a face covering made it difficult to communicate, and more than half felt wearing one made learning more difficult (55%).

The results offer fodder for both sides. Masking does offer psychological comfort to many students during the ongoing pandemic; but many students also believe that masking makes it more difficult to communicate.

The latter point has been only lightly studied. Last year, I covered research showing that masks have been shown through experiments to lower trust. But we barely know how masking is impacting society as a whole and we know next to nothing about how masking is impacting the social development of children, who are still learning how to vocalize words and engage in communication with their peers and adults. There’s a lot we don’t know, and it often seems like we’ve barely made any effort to find out.

Last year, I had the opportunity to work with a talented filmmaker named Eli Steele on a documentary about the closure of a historic pharmaceutical plant in a town in West Virginia.

Eli is deaf. One thing I learned working with him is that even with hearing assistance technology, it’s very important to use good diction when communicating with people who are deaf or hard of hearing. That includes making sure they can read your lips.

As contentious debates about masks heated up in Virginia, I started to wonder how the culture of masking has impacted deaf and hard of hearing Virginians. That led me to the Northern Virginia Resource Center for Deaf & Hard of Hearing Persons (NVRC).

The NVRC has worked with deaf and hard of hearing people for around 34 years, serving as a hub for the community. It operates a number of services, including educational programs and hearing screenings. They stay busy — it’s estimated there are over 100,000 people in Northern Virginia who are hard of hearing. When I reached out to them, they graciously offered to sit down with me and explain how the last two years have transformed the lives of deaf and hard of hearing people.

“There’s something I want to play for you,” Bonnie O’Leary, NVRC’s Director of Community Outreach Programs and a hard of hearing person herself, told me before she played an audio recording for me from her stereo system.

“I want you to listen to a simulation of high-frequency hearing loss,” she said. “Which is what impacts the majority of people within the hard of hearing community, like 26 million Americans who’ve got this problem. And what you’re going to hear, this man as he’s speaking first it will start out with normal hearing you’ll hear like a normal hearing person, then it will go to mild, then moderate, then severe, and then profound high-frequency hearing loss. And as the hearing goes down I want you to imagine what it’s like for someone with that type of a hearing loss to try to understand somebody who’s got a mask on, it maybe like drives the point home in a way.”

I heard a voice reading a sentence. At first, it was clear as daylight what he was saying. But as the line repeated at every stage of hearing loss, it became much more difficult to hear. By the time it got to the last stage, I couldn’t make out any of his words at all.

As someone with normal hearing, listening to the simulation offered a small taste of the world that people who are deaf or hard of hearing live through every day. And the COVID-19 pandemic and the culture of masking that sprung up around it introduced even more challenges to that world.

Eileen McCartin, NVRC’s Executive Director, explained those challenges to me.

“Acoustically, even if you didn’t really think you were hard of hearing before this, now you are,” she told me while gesturing to a surgical mask on the table, “because…of the acoustic properties of this are interfering with the sound going through. So you have that little muffle. And…you also lose the ability to lip read, and the facial expressions, and things like that. So people going into stores and places like that, they get heightened anxiety, if you will. So I have two cochlear implants, so for me usually I use lip-reading as a backup. So I have acoustic ability to receive the sound pretty good but with the masks it’s harder.”

Both McCartin and O’Leary use apps on their smartphones to help them communicate. They showed me Live Transcribe (available on Android phones) and Otter (which you can use on both Android and Apple phones), which offer a way to transcribe what the phone can hear.

O’Leary told me she had surgery in the recent past and had to communicate to an anesthesiologist who had both a face shield and a mask on.

“Imagine being a deaf person having to go to the hospital, or a very hard of hearing person, and they’re all coming at you in masks,” she told me.

In this case, the anesthesiologist was kind enough to take her mask down to allow O’Leary to lip read her (she also downloaded Otter to be able to communicate with her in the operating room).

Public schools have long offered accommodations for deaf or hard of hearing children. These include providing sign language interpreters and/or providing assisted hearing systems that include a teacher pinning a microphone to themselves. But in a culture of masking, these accommodations can only go so far. If most students and staff are masked up — and in Northern Virginia, it’s likely that most of them will be even after the removal of mandates — challenges will remain for deaf or hard of hearing children. The lip-reading they rely on will continue to be obstructed, and masks will continue to muffle the sounds that will be even harder to understand.

To be clear, the NVRC aren’t anti-maskers. In fact, McCartin and O’Leary spoke both told me that they understand the health concerns and tradeoffs that currently exist. They want people to be healthy.

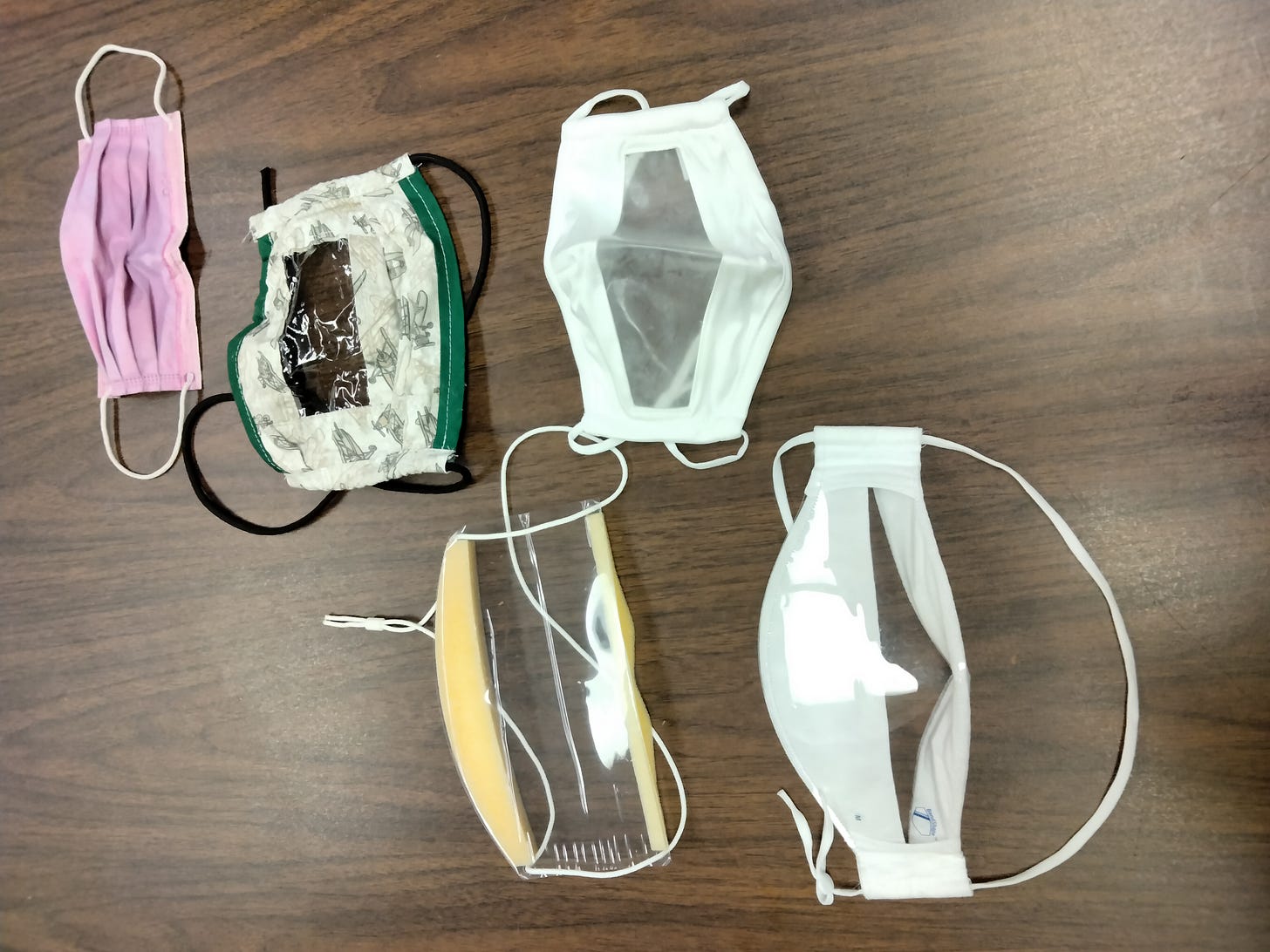

But it’s obvious that there has been too little research done on the social costs of the culture of masking, both on the general public and on groups like the deaf and hard of hearing community. It’s possible, for instance, that moving to transparent or clear masks could help everyone by enabling lip-reading and facial communication again. The NVRC staff showed me some of the clear masks they had on hand.

Of course this would be a challenging transition to make. How many clear masks have you seen during the entire pandemic? I hadn’t seen any until I visited NVRC. Now, many Americans are switching to more advanced N95 masks, which are typically not transparent (although Ford Motor Company announced they will be making clear ones).

Meanwhile, some educational settings are starting to be more mindful about these challenges. Rochester University, for instance, moved to require “surgical, N95, KN95, or KF94 masks (non-cloth masks) to be worn by all students, faculty, staff, and visitors—including those who are fully vaccinated—while indoors on any of the University’s campuses and properties,” but made an exemption for deaf or hard of hearing individuals who may need others to wear a clear face mask. If Ford is able to ramp up the production of its clear N95, there may be a way to satisfy both interests: providing protection for those who continue to want it while doing less to impair facial expressions and lip-reading.

But we can’t seriously tackle any of these challenges until we admit they exist. For months, some have argued that the case for or against masks in various settings is cut and dry, black and white. When we fail to see the gray is when we miss the important realities of many people out there whose voices have gone unheard.